Since the Parkland shooting in February, many white families have been showing their support for gun reform. But will this be enough to make a dent in school shootings? Students of color are calling on white parents to prioritize racial justice over guns

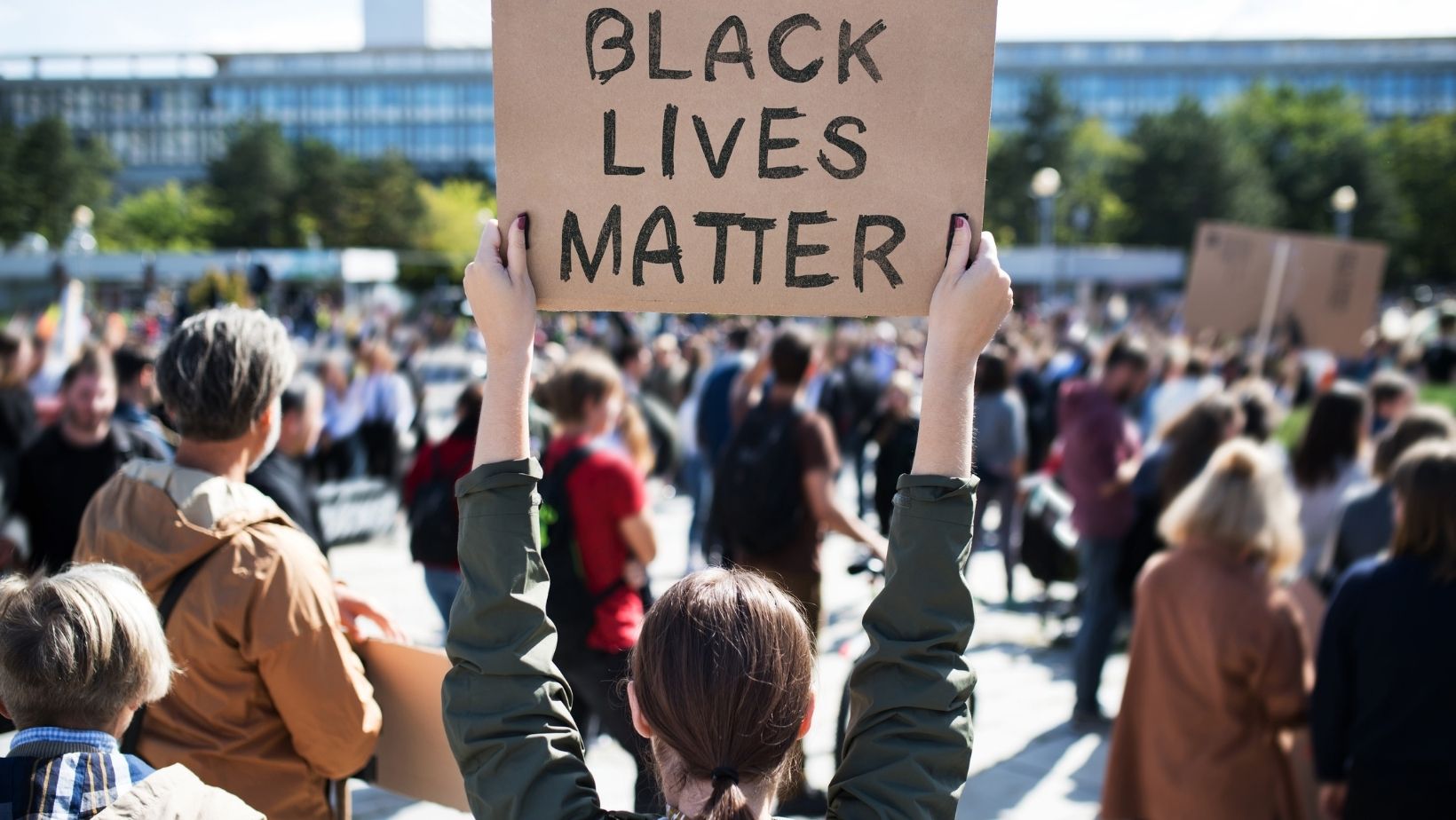

Melinda D. Anderson, a writer, tweeted the day after former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin was sentenced to 22 years in prison for killing George Floyd, saying it “must’ve been a huge relief for many white liberals who can now exhale, inconspicuously remove BLM from their social media profiles, and spend their money on normal summer pastimes rather than on antiracist nonfiction they never reread.”

Derek Chauvin’s sentence must have come as a great relief to many white liberals, who can now sigh, delete BLM from their social media accounts invisibly, and spend their money on regular summer activities rather than anti-racist literature they’ll never read. Hello and good morning.

— @mdawriter (Melinda D. Anderson) 26th of June, 2021

The majority of white Americans are mainly spectators in today’s racial justice movement. What exactly is the issue? Police brutality is on the rise. Who is to blame for this? Derek Chauvin, other white cops, and/or police unions What is expected of the majority of white Americans? Anti-racist nonfiction choices in our book groups, angry social media postings, yard posters.

It’s easy to condemn brutal racial injustice from afar, but it’s obviously not going to be enough to undo the more subtle, deep-seated racist systems that shape American life. This is most evident in our schools, where racial and socioeconomic segregation persists, even in areas where white liberals take pleasure in supporting a broad range of racial justice issues.

Courtney E. Martin, author and activist, recounts her experience of attempting to walk her white parents’ talk on racial justice in her new book, “Learning in Public: Lessons for a Racially Divided America from My Daughter’s School.”

Last week, I published a post for the Washington Post in which I said:

Martin noticed that the kids at their neighborhood school, Emerson Primary, seemed to be nearly completely Black and brown — even as the area grew more white — when her eldest daughter, Maya, started elementary school. It turned out that the majority of her demographic friends had wrangled places for their children in whiter, richer schools in different areas of Oakland. Some lobbied school authorities until they were admitted to more privileged public institutions; others paid $30,000 per year to attend a neighboring private school that prided itself on its progressive ideals and teaching. Their enthusiasm for variety waned at the schoolhouse door, as it did in so many other communities.

“Where did the majority of White youngsters attend school?” Martin is perplexed. “I attended to my local school in the 1980s. Find out where you belong. There was no hassle. I’d never heard of the term’school choice.’

Where did the majority of white children attend school?

“Learning in Public” is an exploration of the political, cultural, social, economic, and other institutions that lie underneath that question. Who gets to plant what and where? Why are our communities so divided? Is selecting a neighborhood a particularly harmful kind of school choice? Is it true that gentrification in mainly Black and brown metropolitan areas leads to school integration, and that this is always beneficial for the children in such communities?

Martin shows that delving further into the origins of segregated neighborhood schools reveals a wealth of information. To begin with, academics and authors like as Ta-Nehisi Coates, Richard Rothstein, and Tim DeRoche have convincingly shown that American segregation — both of neighborhoods and the schools allocated to them — is mainly the result of deliberate governmental policy. Racial housing segregation was formalized into zoning regulations by local governments. Local governments were “redlined” as hazardous locations for mortgage financing, and racially discriminatory covenants were allowed to be put in place, preventing non-white families from buying homes in certain regions.

So, no matter how natural neighborhood schools seem to be, the site of each child’s “planting” is usually determined by a complex set of structural factors that decide which families have access to which homes in which areas. Excessively affluent white children are not born into mostly white exurban areas by accident. They’re there because of their families’ intergenerational riches — and their families’ ability to navigate long-standing housing rules that preserve that money. The unreflective appreciation of these deep, historical, systemic biases favoring the affluent is best characterized as privileged excitement for local schools.

Nonetheless, in recent years, a large number of white families have followed the regionalization of economic opportunity into a small number of U.S. metro areas, complicating rather than bucking those biased policy structures. Martin’s book delves into the tense conflict that arises when gentrifying white families undertake the task of desegregating urban areas and run across manifestations of American educational inequity in their new surroundings. (Spoiler: their excitement for varied urban areas does not necessarily extend to their diverse new urban neighborhood schools.)

In a time of gentrification, school integration is more important than ever.

“Learning in Public” considers the ramifications of this period in American city gentrification, a period that may put fresh strains on long-standing attempts to promote educational equality via school integration. On the one hand, the present offers a window of opportunity: when more highly educated, affluent, and frequently white families move into metropolitan areas of color, it becomes much simpler for school administrators to accommodate diverse enrolment. Schools may use the increased closeness of kids from a variety of backgrounds to coordinate school desegregation as communities diversify. Unlike many previous initiatives, this new environment does not need multi-school district coordination agreements or major new school transportation networks. There are several groups of students living in close proximity to one another. All that is left is to assist them in learning together.

Gentrification, on the other hand, is essentially a process in which affluent families use social and material capital to gain more of both. While gentrification often results in an inflow of public and private investment, most communities struggle to guarantee that these new resources reach long-term inhabitants. Indeed, when the presence of highly educated, affluent, typically white families drives up the cost of living in a community — especially local property costs – low-income people or families of color are often displaced. Few fair results could be anticipated from such a fundamentally inequitable procedure.

Furthermore, even if gentrification eliminates physical proximity barriers to school desegregation, the practical divide between living and studying together remains enormous. In gentrifying areas, privileged families often use their financial and social advantages to secure racially and/or socioeconomically separated school settings for their children. This dynamic manifests itself in a variety of ways. For example, when a community gentrifies, its allocated neighborhood school may be gradually “colonized” by privileged children and families until less-affluent families can no longer afford to live within the campus’ enrollment zone. Alternatively, wealthy families may use current choice mechanisms to obtain places in elite magnet schools, private schools, gifted and talented programs, or non-neighborhood public schools for their children.

At a time when urban white families are demonstrating renewed enthusiasm for the cause of racial justice, it’s time to question whether they’re ready to go beyond talking about it and start living it. There is a lot to do. Local officials may follow Minneapolis’ and other cities’ example and change zoning rules to make it simpler to construct additional urban housing. Education authorities may extend public school choice programs with diversity objectives that help families integrate and decouple school attendance from their ability to afford housing in certain regions. White, affluent urban families, maybe most importantly, can incorporate public schools as part of what it means to fully integrate into their diverse new neighborhoods.